Hazy Trauma: The Legacy of Medieval Brutality in White-American Violence

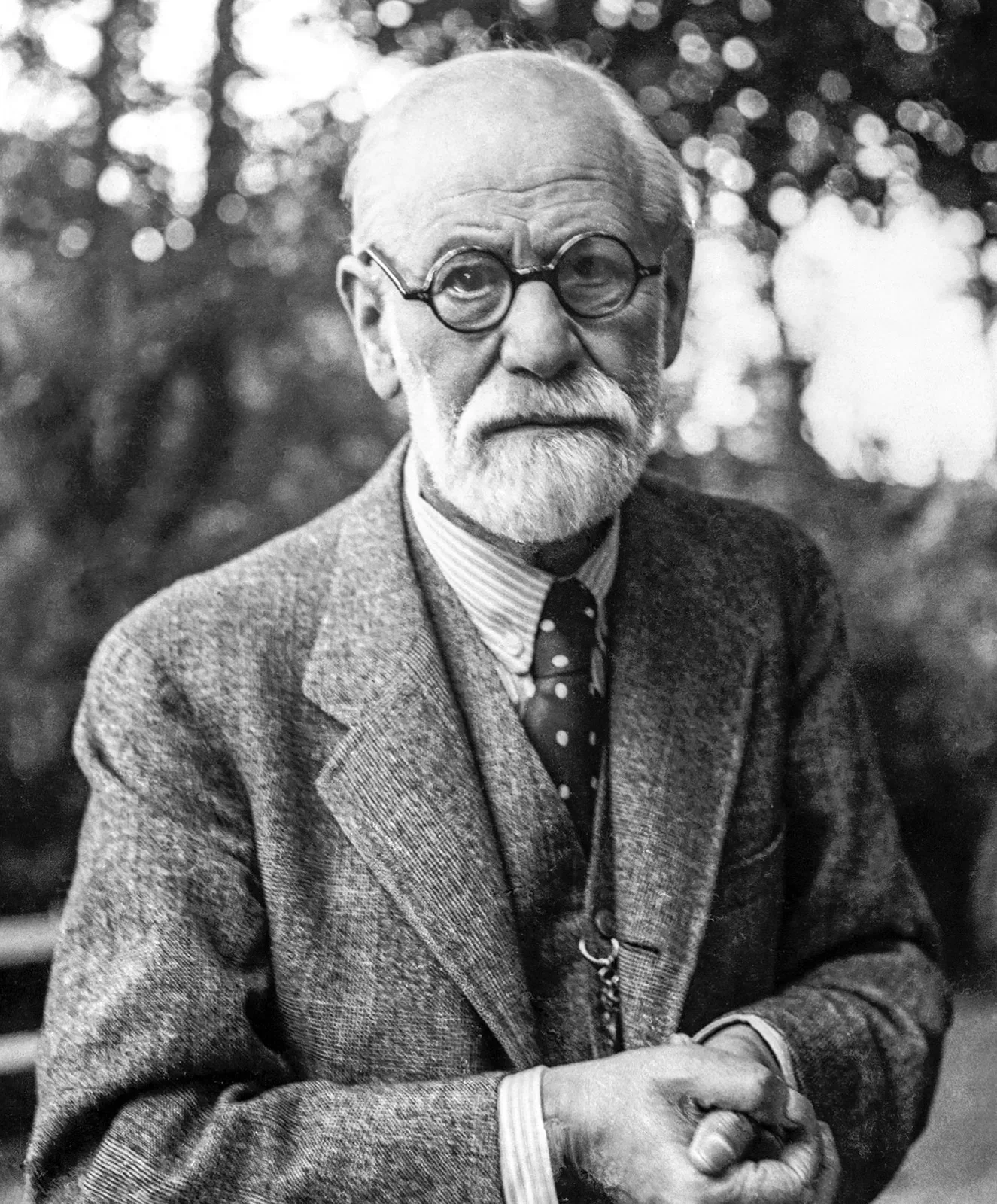

Sigmund Freud

As a first-year graduate student, studying to become a clinical social worker, I have been surprised by how relatively young the tradition of psychoanalysis is. Sigmund Freud was born in 1856 and began theorizing and writing about the human psyche in the 1890s. Freud died in 1939. His daughter, Anna, developed his theory, and over the course of the 20th century, other theorists emerged, all attempting to shed light on the complexity of human psychology.

I am now a student in a field that has only been around for 135 years. Before this, I was a pastor in the Christian tradition, a practice that has been around for 2,000 years. While theologians and biblical scholars continue to write and think about Christianity, there is an established orthodoxy that must be contended with. While Freud and his theories are considered foundational, they certainly do not demand religious-like devotion. In fact, psychology, as a social science, relies on continual research and development.

I’m thankful to be in a field that is dynamic and growing. I am particularly encouraged by the cross-pollination between psychology and neuroscience, and by our ever-expanding understanding of human cognition. Thanks to this collaboration, we, future clinicians, are being immersed in an ever-expanding field of research around the impacts of trauma on individuals and groups.

It wasn’t until 1980 that PTSD was added to the DSM. Trauma studies began in the 1990s and continued through the early 2000s. In 2014, the wildly popular book The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk introduced the masses to the concepts of trauma, in particular its propensity to be inherited across generations.

In just ten years, the trauma studies field has heavily critiqued van der Kolk’s seminal work, mainly because he ignores the broader social and political contexts of violence that contribute to the development of trauma. These critiques are evidence of the rapid growth of trauma theory and the relatively recent introduction of trauma into our cultural lexicon.

Thankfully, there are people like Resmaa Menakem—who studied under van der Kolk—who have taken up the task of expanding our understanding of trauma. In 2017, Menakem released his book My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies. Many now consider My Grandmother’s Hands to be the necessary replacement to The Body Keeps the Score as it successfully integrates our understanding of trauma alongside the systemic and cultural nature of racism and white supremacy.

Resmaa Menakem

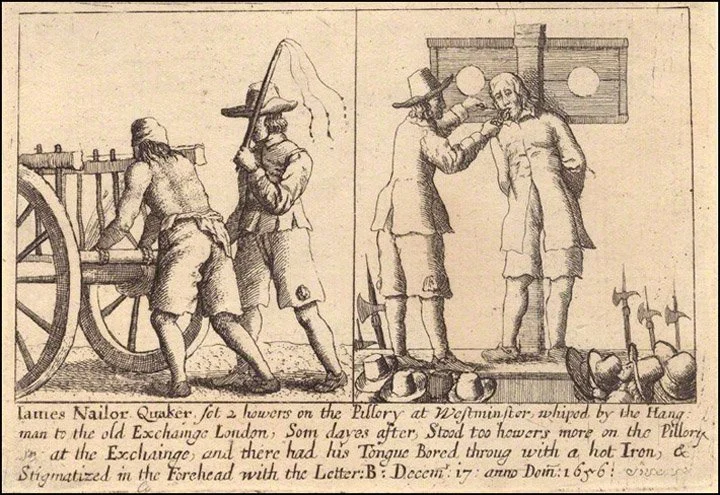

Chapter four of My Grandmother’s Hands is titled, “European Trauma and the Invention of Whiteness.” The chapter opens with a quote from Janice Barbee, “What white bodies did to Black bodies they did to other white bodies first.” In this chapter, Menakem gives a brief history of the brutal realities of medieval Europe. He writes, “People were routinely burned at the stake for heresy, a practice that began in the twelfth century and continued through 1612. Torture was an official instrument of the English government until 1640.” Torture and brutality became a public spectacle as a means of warning and deterrence to wannabe criminals or heretics.

As a former Quaker pastor, I am intimately familiar with the legacy of English/European brutality. You cannot tell the story of Quakers without talking about the history of its earliest followers becoming targets of imprisonment, torture, and public shaming. What’s more, you cannot tell the history of America without mentioning the influx of religious and political refugees from England. The entire state of Pennsylvania was founded as a Quaker “utopia,” established as a haven from the brutality of religious-based persecution. Menakem writes, “Many of the English who colonized America had been brutalized, or had witnessed great brutality firsthand.” He puts a fine point on this reality when he says, “For all their talk of the new Jerusalem, the Pilgrims and Puritans were not explorers. They were refugees fleeing imprisonment, torture and mutilation” (Menakem, 2017, 59-60)

You would think that the story of America, especially as a place of refuge from such brutality, would be one of non-violence, of gentleness, and hope. But we know that is not the story. Our cozy images of Indigenous peoples and pilgrims sharing a Thanksgiving meal are but a myth we tell our children to gloss over the fact that a traumatized people brought their trauma with them to the colonies. Mekankem pleads with us, White folks, to contend with the brutality of colonization and chattel slavery that was unleashed on Indigenous people and those kidnapped from Africa. He writes, “Did over ten centuries of medieval brutality, which was inflicted on white bodies by other white bodies, begin to look like culture?” (Menakem, 2017, 61).

And what about this so-called culture? There is a term, hazy trauma, which is the manifestation of trauma that cannot be traced back to any single event. Menakem notes that hazy trauma is often unhealed trauma “affecting many other bodies over time.” Unhealed trauma can become a family norm, “and if it gets transmitted and compounded through multiple families and generations, it can start to look like culture.” (Menakem, 2017, 39).

Have we not inherited this culture? Have we not perpetuated it to the point that we cannot even begin to have a productive conversation about police brutality or the prevalence of gun violence in this country? Are we continuing to live in the hazy trauma of the brutality of our ancestors, a “haze” that has become a pervasive part of White culture, so that we don’t know who we are without it?

Ruby Sales

I was on a Zoom call with the civil rights activist Ruby Sales when she asked our small group of white people, “What is it about white folks that y’all must brutalize Black bodies?” She asked us this question just days after a white police officer smashed his knee into the neck of George Floyd, murdering him in the streets as he cried out for his mother.

I have been in rooms with white folks who say, “That happened so long ago, don’t you think it is time for us to move on?” I know that white people continue to reject the systemic nature of racism. They label such truths as “woke nonsense” while also claiming they don’t see race and are certainly not racist. Many of these same people proudly voted for a President who utilized racist dog whistles to generate panic to win an election, and assured us there were definitely “good guys” in the crowd of white supremacists who proudly marched through the streets of Charlottesville.

I am daily surrounded by high schoolers in suburban Portland, Oregon, who are influenced by podcasters and social media presences that stoke racial fears about the “loss of white culture.” White supremacy is being actively seeded in the next generation, and with it, the cultural legacy of violence and brutality that we appear to have accepted as our destiny.

When will we be courageous enough to have conversations that are centuries overdue? May it begin with each of us contending with the legacy of trauma in our lives, working towards healing, and truly altering the direction of our collective future together.